Fluidic Echo

A cultural wastewater landscape

Urban Design Strategy

Willets Point, Queens, New York City

Fluidic Echo explores the sewerage infrastructure of Queens, its current negative cultural connotation, and its potential to exist beyond the framework of its function. By negotiating a new relationship between waste, human habitation, and remediation, the project turns the invisible wastewater treatment process into a sensible landscape.

Because sewerage infrastructure is veiled – either purposefully hidden from view or seamlessly entwined with other parts of the built environment – but underlies vast territories, it’s difficult to examine and pinpoint how it impacts our lives. It’s also difficult to ponder what potential sewerage has as a benefit to the long-term vitality and health of cities, since it’s often inaccessible. The failure to identify these problems and potentials is a lost opportunity for planners and designers. However, if we consider sewerage infrastructure as a matter of concern rather than just the matter of waste, then it can become part of a broader dialogue where its sensible and social realities and effects are as important as its engineering function.

Thus, Fluidic Echo’s design strategy takes the form of a “plastic ecology” – a malleable and simultaneous combination of ecological infrastructures and cultural programs that stimulate the prospects of the bleak and contaminated conditions of Willets Point. The mechanical advantage of this strategy allows the self-contained system made up of intersecting parts and processes to be accessed by the public, overcoming the schism between waste and habitation. Each step is varied and operates through graduating scales of exchange, incorporating elements designed to operate individually and in unison. As a synthetic wastewater cultural landscape, these infrastructures suggest new forms of social life and aesthetic experience.

![Sewersheds + Infrastructure]()

![Sewerage Infrastructure]()

![Infrastructural Pockets]()

![Heat Map of 311 Complaints and Frequent Floods]()

The mapping produced sought to access and understand the sewer infrastructure in Queens, its relationship to the pattern of urbanization aboveground, and where sewerage may become accidentally sensible due to infrastructural failure. This is done by examining sewersheds, networks of pipes and discharge points, intersections and pockets formed by sewerage, and heat maps that distill the areas that tend to be the most vulnerable or compromised through the collection of complaint calls and the neighborhood’s relationship to topography.

![]()

This combined map of the previous information strategically points to areas of concern and potential exploration in Queens.

![]()

Google Earth was then utilized to explore where waste and sanitation becomes sensible in the borough, most notably in the previously highlighted areas of concern. This uncovered evidence in the built environment such as the curious excavation of sewerage pipes and the rarely seen objects that compromise it, the use of glass and plastic bottles as lawn decorations, and the way communities shelter their waste bins with iron fences or brick. This exploration led me to further analyze a specific typology that highlights sewerage the most in urban areas, the wastewater treatment plant.

![]()

![]()

(Left) These are the four wastewater treatment plants in Queens, and utilizing Kevin Lynch’s five qualities for an image of the city, a similar logic is applied to these plants in effort to uncover patterns that showcase how waste both becomes legible and demands legibility. These urban chunks are a very small portion of what keeps urban spaces well-managed, but their operations and organization could be interpolated in Fluidic Echo.

(Right) The material inputs, outputs, and processes of the treatment plants are documented to uncover phenomenological opportunities for intervention. The 14 treatment plants in New York City receive 1.3 billion gallons of influent every day and undergo a five-stage 10 hour long process that mimics how natural landscapes purify water before it is then discharged as clean water back into rivers. But there are certain leftover materials and sensations, such as waste, biosolids, odor, and steam, that could potentially be leveraged as building blocks for the project.

![]()

With wastewater treatment plants in mind, now there were a series of formal precedents that could be further studied in order to enact an urban design proposal. But rather than taking the form of a discrete object or single venue in the center of the Iron Triangle in the form of a traditional plant, Fluidic Echo utilizes the idea of a loop to create a fully accessible circuit that activates the entire site and its surrounding context through a cultural wastewater landscape.

![Floodplains]()

![Sewersheds + Sewerage Infrastructure]()

![Zoning]()

Studies of the existing conditoins of Willets Point.

![Preliminary Geometry of the Loop]()

![Adjacent Programs]()

![Circulation]()

![Phytoremediative Point Grid]()

![Phytoremediative Point Grid]()

![Identifying Existing Industrial Vacancies]()

![Lynchian Logic]()

Series of formal and conceptual studies that led to the proposal’s implementation.

![]()

![]()

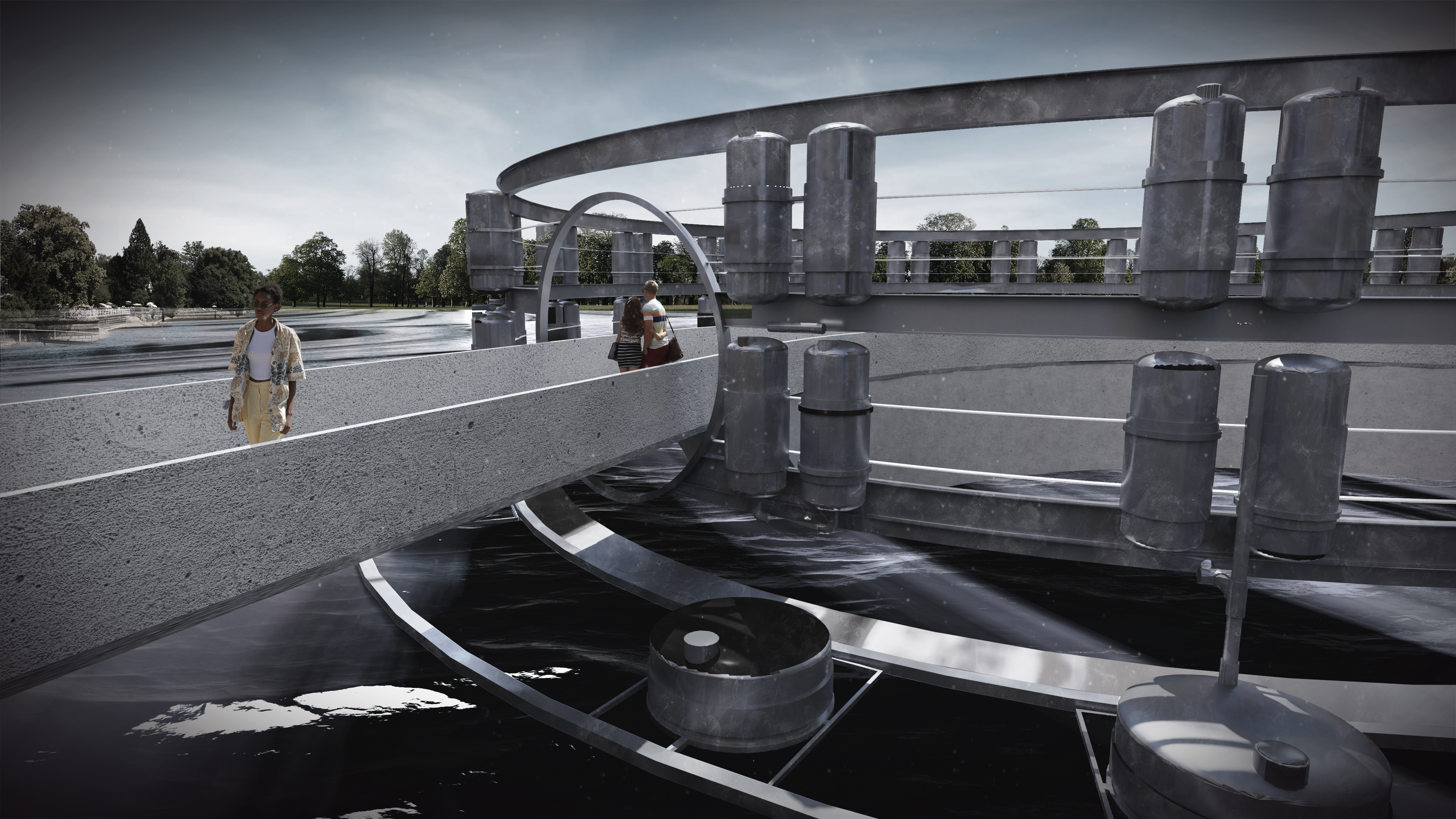

The loop thus presents itself as a re-distribution of the typical wastewater plant. Each structure and phase that was previously documented is spread out and linked by a winding pathway that sutures public life into public works, allowing the fluidic devices to be enjoyed culturally and recreationally. In its final realized form, the project explores the importance of bringing the invisible processes of wastewater treatment into the visible public space

![]()

![]()

![]()

The top half of the project features a water-based experience. By extending Willet's Point to the North and into Flushing Bay, the community is directly connected to the water, reconciling the bay as a new public and productive space. This comes in the form of a new recreational promenade, docks, observation deck, gardens, pools, and more.

![]()

Biosolid mounds, where locals are free to grab the environmentally sustainable and nutrient-rich byproduct of wastewater for their own gardening or construction purposes.

![]()

The bottom half of the project takes inspiration from the Flushing Meadow Corona Park to the South and the residential areas to the East and collapses them to create a new natural and cultural district. This includes an aquarium, public lawns, a museum, an apartment building, and various educational wastewater programs that link them together.

![]()

The desalination station, where water from the Flushing Creek is purified, cleansed, and distributed to other programs of the site that may utilize it for various means.

![]()

![]()

Willets Point, Queens, New York City

Fluidic Echo explores the sewerage infrastructure of Queens, its current negative cultural connotation, and its potential to exist beyond the framework of its function. By negotiating a new relationship between waste, human habitation, and remediation, the project turns the invisible wastewater treatment process into a sensible landscape.

Because sewerage infrastructure is veiled – either purposefully hidden from view or seamlessly entwined with other parts of the built environment – but underlies vast territories, it’s difficult to examine and pinpoint how it impacts our lives. It’s also difficult to ponder what potential sewerage has as a benefit to the long-term vitality and health of cities, since it’s often inaccessible. The failure to identify these problems and potentials is a lost opportunity for planners and designers. However, if we consider sewerage infrastructure as a matter of concern rather than just the matter of waste, then it can become part of a broader dialogue where its sensible and social realities and effects are as important as its engineering function.

Thus, Fluidic Echo’s design strategy takes the form of a “plastic ecology” – a malleable and simultaneous combination of ecological infrastructures and cultural programs that stimulate the prospects of the bleak and contaminated conditions of Willets Point. The mechanical advantage of this strategy allows the self-contained system made up of intersecting parts and processes to be accessed by the public, overcoming the schism between waste and habitation. Each step is varied and operates through graduating scales of exchange, incorporating elements designed to operate individually and in unison. As a synthetic wastewater cultural landscape, these infrastructures suggest new forms of social life and aesthetic experience.

The mapping produced sought to access and understand the sewer infrastructure in Queens, its relationship to the pattern of urbanization aboveground, and where sewerage may become accidentally sensible due to infrastructural failure. This is done by examining sewersheds, networks of pipes and discharge points, intersections and pockets formed by sewerage, and heat maps that distill the areas that tend to be the most vulnerable or compromised through the collection of complaint calls and the neighborhood’s relationship to topography.

This combined map of the previous information strategically points to areas of concern and potential exploration in Queens.

Google Earth was then utilized to explore where waste and sanitation becomes sensible in the borough, most notably in the previously highlighted areas of concern. This uncovered evidence in the built environment such as the curious excavation of sewerage pipes and the rarely seen objects that compromise it, the use of glass and plastic bottles as lawn decorations, and the way communities shelter their waste bins with iron fences or brick. This exploration led me to further analyze a specific typology that highlights sewerage the most in urban areas, the wastewater treatment plant.

(Left) These are the four wastewater treatment plants in Queens, and utilizing Kevin Lynch’s five qualities for an image of the city, a similar logic is applied to these plants in effort to uncover patterns that showcase how waste both becomes legible and demands legibility. These urban chunks are a very small portion of what keeps urban spaces well-managed, but their operations and organization could be interpolated in Fluidic Echo.

(Right) The material inputs, outputs, and processes of the treatment plants are documented to uncover phenomenological opportunities for intervention. The 14 treatment plants in New York City receive 1.3 billion gallons of influent every day and undergo a five-stage 10 hour long process that mimics how natural landscapes purify water before it is then discharged as clean water back into rivers. But there are certain leftover materials and sensations, such as waste, biosolids, odor, and steam, that could potentially be leveraged as building blocks for the project.

With wastewater treatment plants in mind, now there were a series of formal precedents that could be further studied in order to enact an urban design proposal. But rather than taking the form of a discrete object or single venue in the center of the Iron Triangle in the form of a traditional plant, Fluidic Echo utilizes the idea of a loop to create a fully accessible circuit that activates the entire site and its surrounding context through a cultural wastewater landscape.

Studies of the existing conditoins of Willets Point.

Series of formal and conceptual studies that led to the proposal’s implementation.

The loop thus presents itself as a re-distribution of the typical wastewater plant. Each structure and phase that was previously documented is spread out and linked by a winding pathway that sutures public life into public works, allowing the fluidic devices to be enjoyed culturally and recreationally. In its final realized form, the project explores the importance of bringing the invisible processes of wastewater treatment into the visible public space

The top half of the project features a water-based experience. By extending Willet's Point to the North and into Flushing Bay, the community is directly connected to the water, reconciling the bay as a new public and productive space. This comes in the form of a new recreational promenade, docks, observation deck, gardens, pools, and more.

Biosolid mounds, where locals are free to grab the environmentally sustainable and nutrient-rich byproduct of wastewater for their own gardening or construction purposes.

The bottom half of the project takes inspiration from the Flushing Meadow Corona Park to the South and the residential areas to the East and collapses them to create a new natural and cultural district. This includes an aquarium, public lawns, a museum, an apartment building, and various educational wastewater programs that link them together.

The desalination station, where water from the Flushing Creek is purified, cleansed, and distributed to other programs of the site that may utilize it for various means.